Elaine, Let’s Get the Hell Out of Here

June 29 - August 18, 2017

Deborah Anzinger, Alex Bradley Cohen, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Ralph Lemon, Al Loving, Rosemary Mayer, Joan Mitchell, Sheila Pepe, Sable Elyse Smith, Joan Snyder, Vanessa Thill, Molly Zuckerman-Hartung

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Installation View, Elaine, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here, 2017

-

Sheila Pepe

On to the Hot Mess, 2017

Nautical towline, rope, shoe laces, and hardware

Dimensions variable -

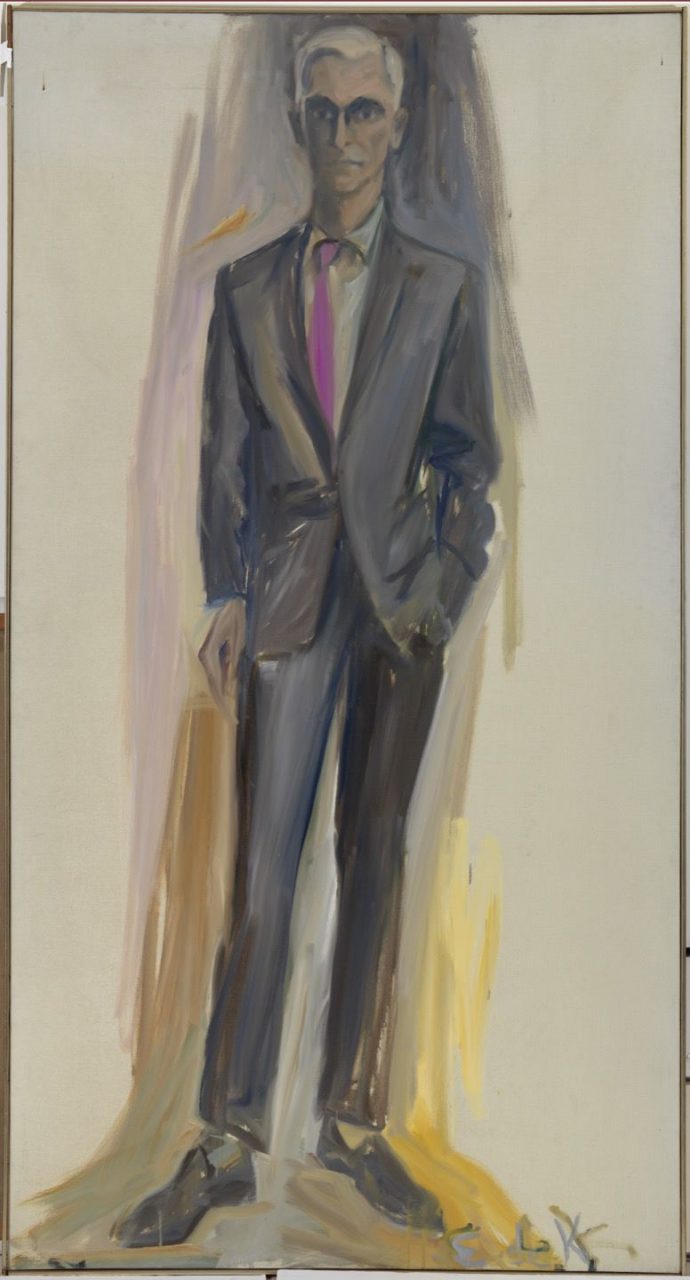

Elaine de Kooning

Edwin Denby, 1960

Oil on canvas

90 x 49 inches

Photograph by Mark Gulezian -

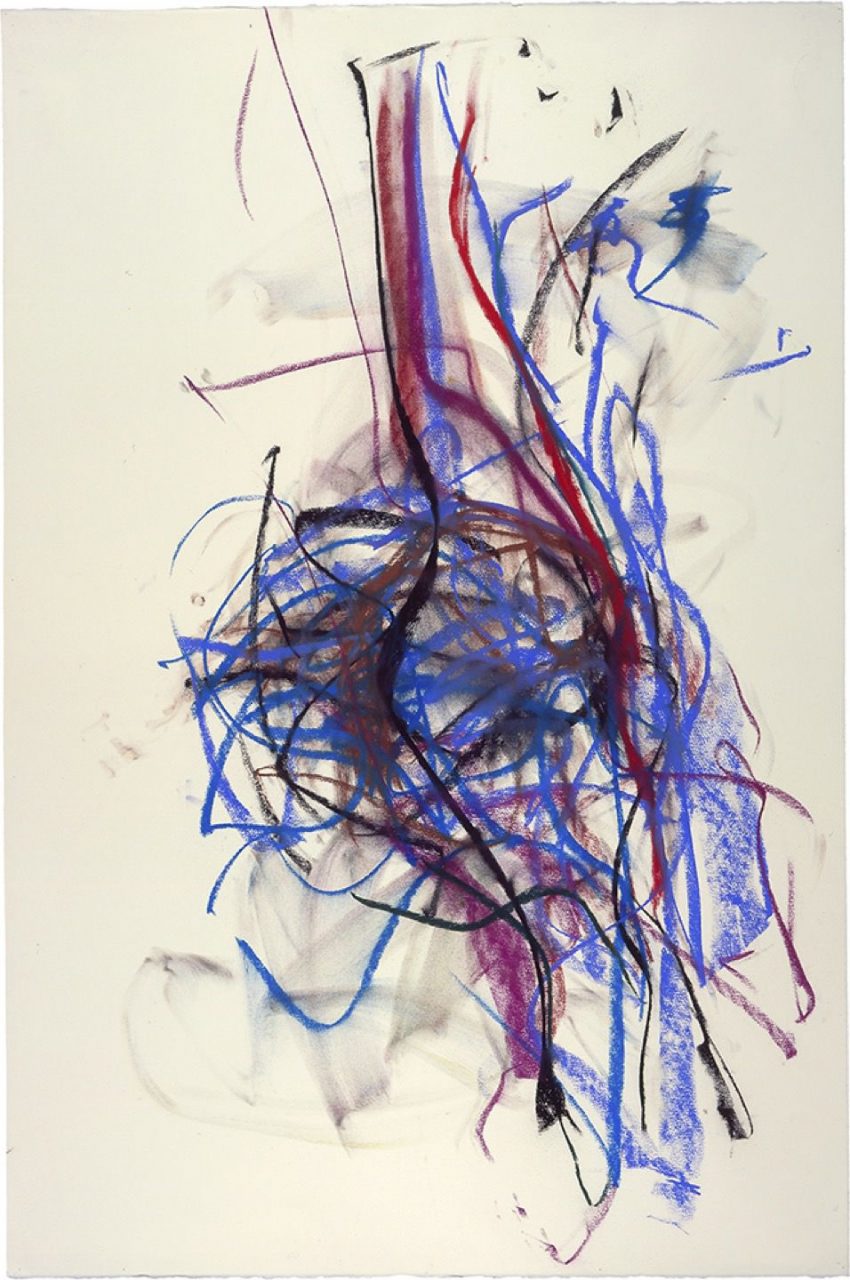

Joan Mitchell

Untitled, 1991

Pastel on paper

47 5/8 x 31 1/2 inches

Collection Joan Mitchell Foundation

© Estate of Joan Mitchell -

Grace Hartigan

Hollywood Interior, 1993

Oil on canvas

66 x 78 inches -

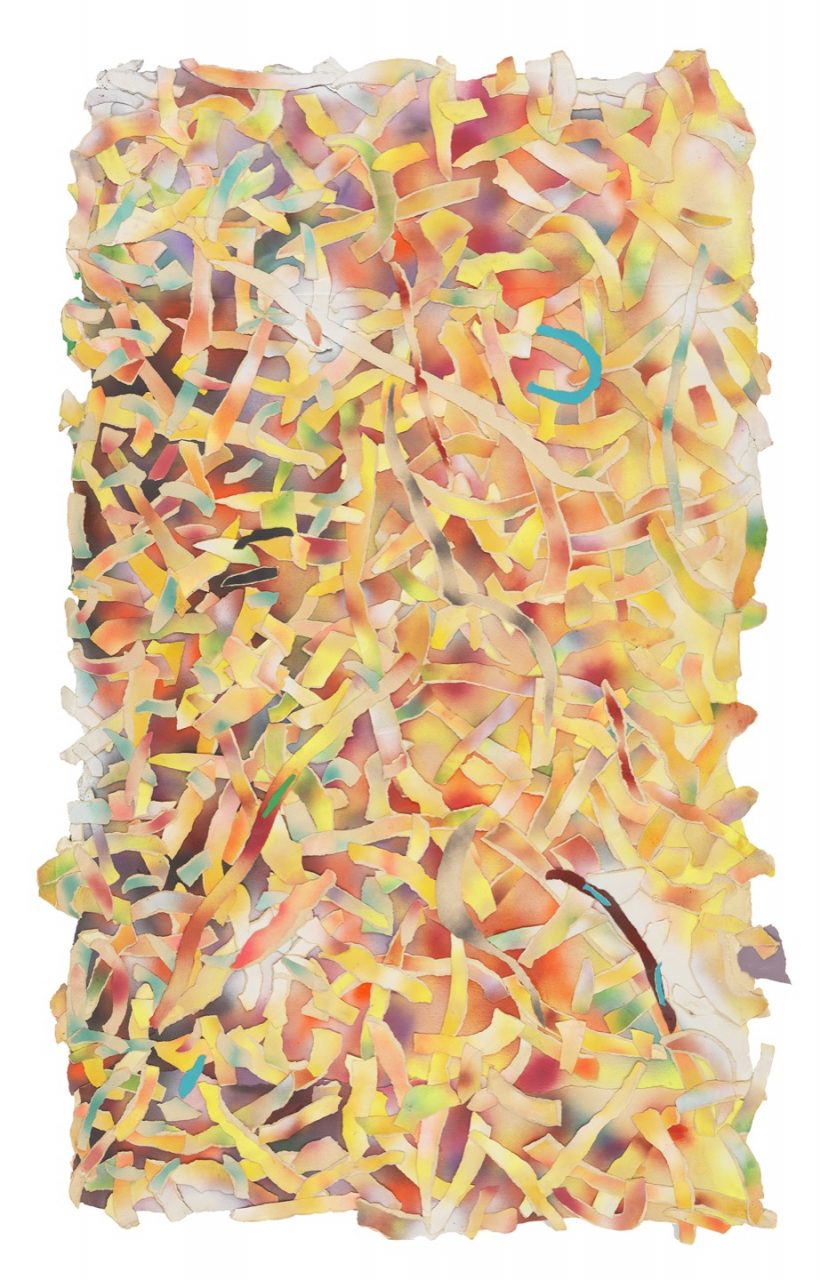

Al Loving

Untitled, 1976

Paper collage

53 x 30 inches -

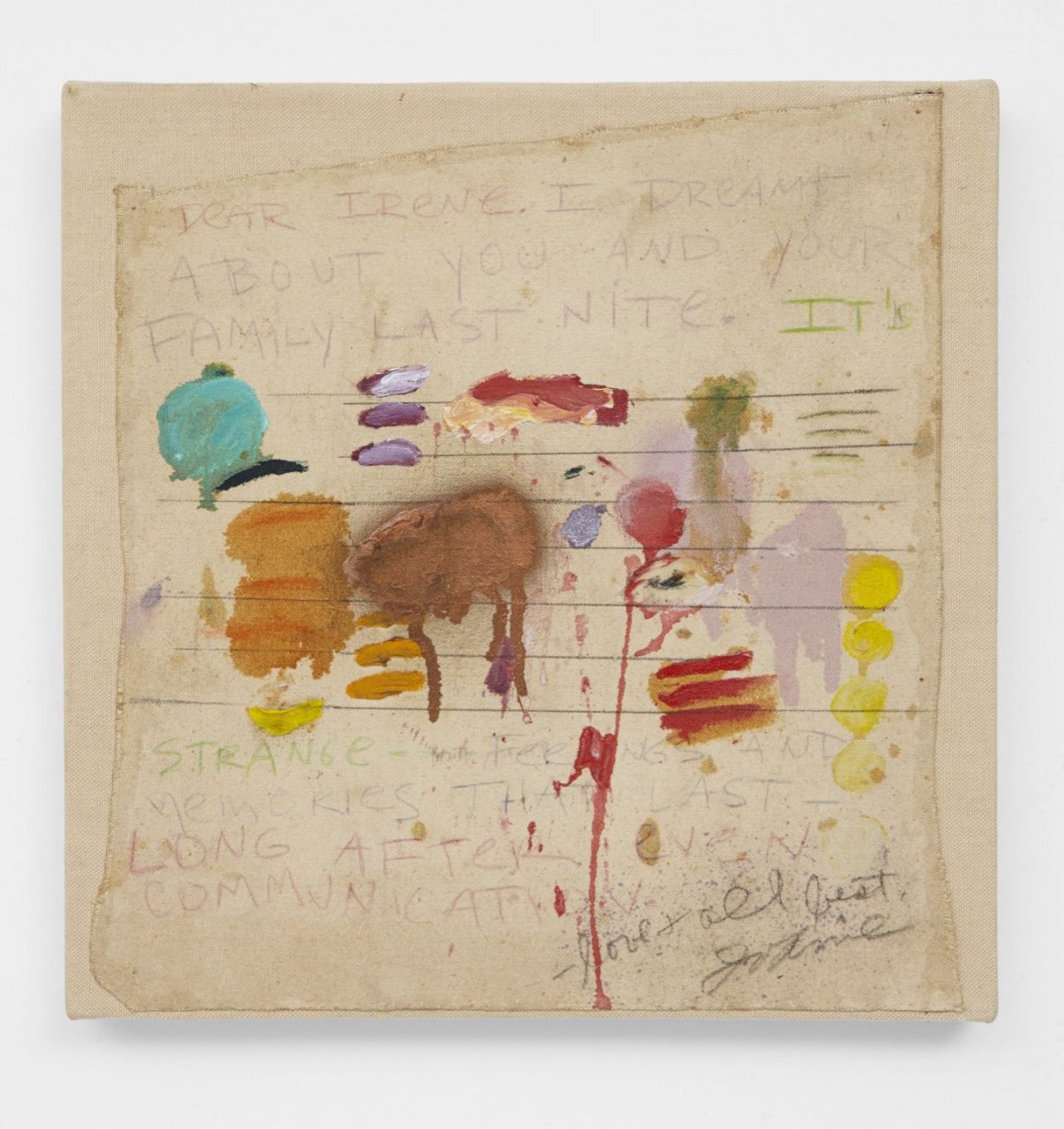

Joan Snyder

Dear Irene, 1970

Oil, acrylic, pencil and spray paint on canvas

15 x 15 inches -

Alex Bradley Cohen

Tariq, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

44 x 40 inches -

Rosemary Mayer

Balancing, 1972

Fabric, cords, and acrylic rods

126 x 96 inches -

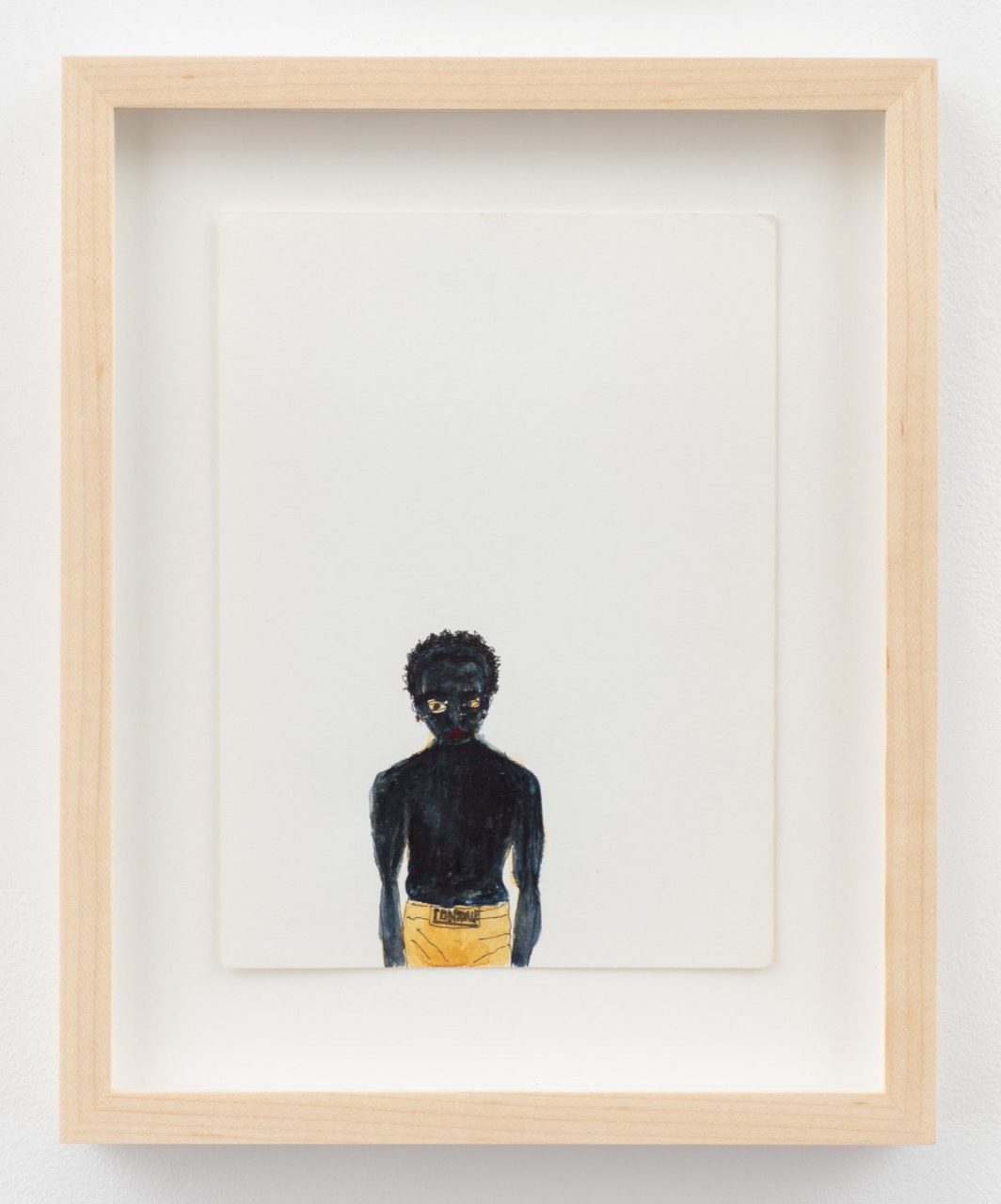

Ralph Lemon

Miles, 2007

Ink and watercolor on paper

7 x 5 1/2 inches -

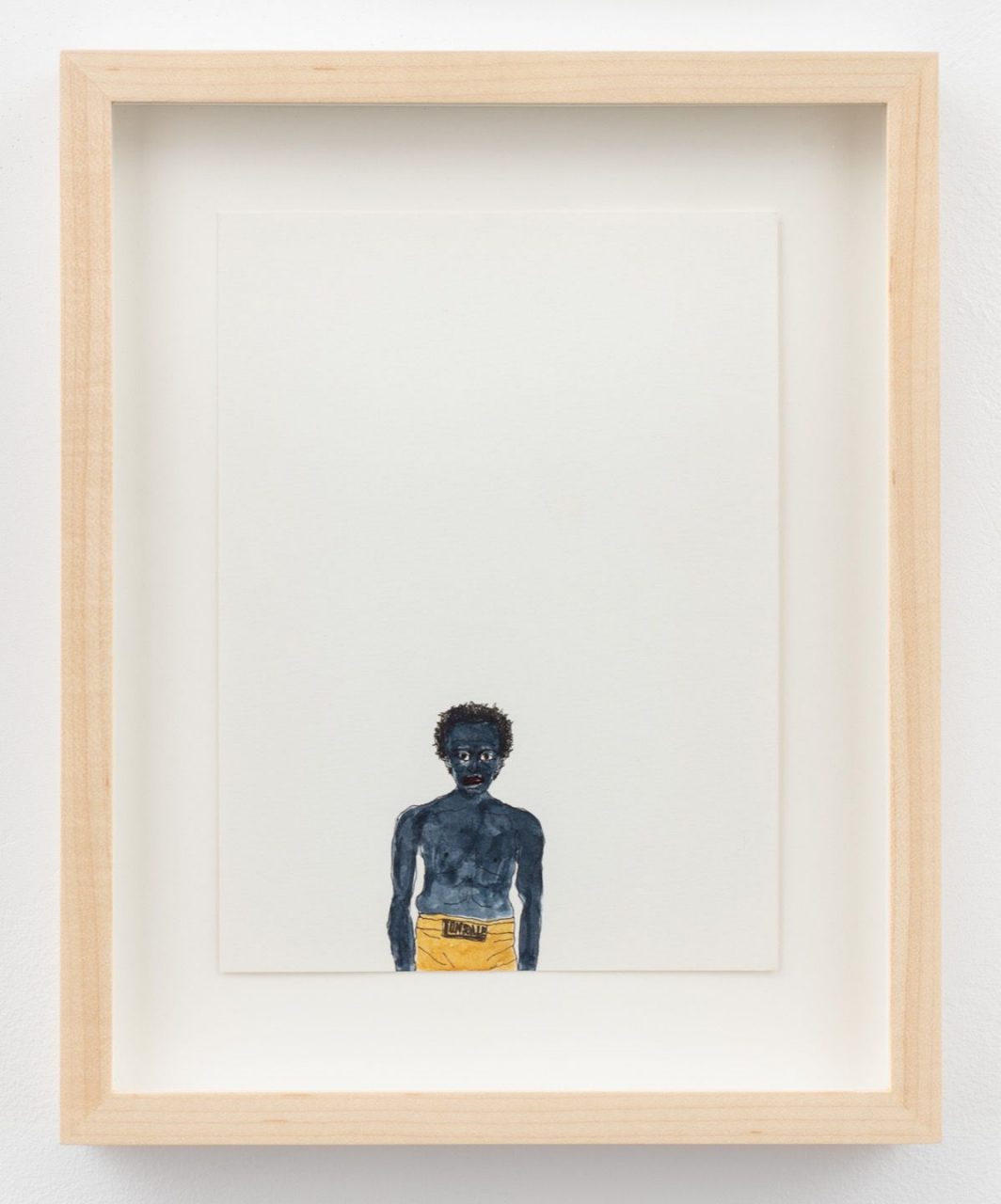

Ralph Lemon

Miles, 2007

Ink and watercolor on paper

7 x 5 1/2 inches -

Molly Zuckerman Harthung

Lurch, 2009-14

Acrylic, oil, enamel, spray paint on sewn tshirts, coat liner, wool, canvas, and dropcloth

112 x 69 inches -

Deborah Anzinger

I told you, 2017

Acrylic and mirrored glass on canvas

72 x 54 inches -

Vanessa Thill

Petro-Queen II, 2017

Pigments, inks, coffee, fabric dye, engine degreaser, hair products, cleaning fluid, spices, glue, and epoxy resin on paper

60 x 48 inches -

Sable Elyse Smith

Untitled, 2012

Single channel video TRT: 4:56

Edition of 3 plus AP

Press Release

In the January 1971 issue of ARTnews, the magazine asked Elaine de Kooning and seven other artists to respond to an article they were publishing in the same issue: Linda Nochlin’s now-iconic essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Right away, de Kooning took issue with the term “women artists,” using an anecdote to explain.

“I was talking to Joan Mitchell at a party about 10 years ago when a man came up to us and said, ‘What do you women artists think…’ Joan grabbed my arm and said, ‘Elaine, let’s get the hell out of here.’” In the spirit of Joan and Elaine’s party exit, this show brings together artists working across disparate contexts and mediums whose practices take complicated and resistant positions on identity.

The exhibition begins with Mitchell and de Kooning and traces an attitude of refusal through successive generations of artists with kindred aesthetic gestures and interests. All of the artists in the show employ certain modernist strategies, but for their own means and with their own agendas. In disallowing materials, colors, and strokes from being pinned down, the work manifests a politicized expressionism.

Across the five generations of artists represented here, one can chart when and why certain labels (abstraction, expressionism, portraiture; gender, race, sexuality; drip, stain, pour) have historically been embraced or rejected. More importantly, however, the work exemplifies that sorting through all of the categories one might use to circumscribe a work of art is a messy and mercurial business. Each of the works on view remain ambivalent, even prickly, as they make and unmake the capacious boundaries of modernism.

Beyond gendered constraints, Joan Mitchell (1925-1992) was also skeptical of tethering abstraction. “Abstract is not a style … it's an ambivalence of forms and space,” she said in a 1986 interview. Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) and Grace Hartigan (1922-2008) too challenged the bounds of AbEx. Not only did both paint figuratively, but they rubbed shoulders with the queer subculture of the New York School. Elaine de Kooning’s portrait captures poet, dance critic, and friend Edwin Denby who penned several poems about his nighttime walks with the de Koonings. Grace Hartigan, as part of the second generation of the AbEx, was a close friend of poet and MoMA curator Frank O’Hara who dedicated his famous “In Memory of My Feelings” to her.

A decade later, second-wave feminists embraced the moniker “woman artist” as a category of empowerment. Rosemary Mayer (1943-2014) was a founder of A.I.R. Gallery and worked in the consciously feminist medium of fabric when many artists were reclaiming craft and women’s work. Yet, her interest in fabric was also born from a fascination with Italian Mannerism, specifically the work of Florentine painter Pontormo, whose diary she translated into English for the first time. Joan Snyder (b.1940), who was painting at a time when the medium was spurned by her feminist contemporaries, linked abstraction to queer desire as evidenced in Dear Irene. The strokes in my paintings speak of my life and experiences,” she wrote in 1972. At the same time, Black artists were dealing with similar criticism from their peers about the political efficacy of abstract art. In a 1985 interview, Al Loving (1935-2005) explained the decision to move on from his early hard-edged abstraction: “The whole period of doing this geometric art conflicted with civil rights. There was no way to work that out so the pictures kept moving at their own rate.”

The next generation of artists began their careers at the outset of postmodernism. For queer artists working at this time, identity was bound up with refusal (Lee Edelman has written that “the efficacy of queerness lies in its very willingness to embrace this refusal of the social and political order”). Ralph Lemon (b.1952), widely known as a choreographer and dancer, has an extensive art practice, much of which is drawings. Here he depicts Miles Davis in his boxing attire. Speaking of his multi-disciplinary practice, Lemon has recently said that he “refuse[s] the way the work gets coded” and that he “has taken on an identity politic of being culturally dysfunctional.” Working primarily in crochet and fiber art, Sheila Pepe (b.1959) utilizes the materials of second-wave artists at the same time that she nods to modernist formal concerns in her impermanent installations. Pepe terms her work “hot mess formalism,” advancing a critique of canonicity and high/low binaries.

Coming of age in the 90s, Deborah Anzinger (b.1978) and Molly Zuckerman-Hartung (b.1975) address third-wave and postcolonial concerns. Anzinger, who is based in Kingston, Jamaica, uses abstraction to consider the site of her home country and the trope of woman-as-landscape in a Caribbean context. She posits slipperiness as a tool for survival in a postcolonial setting and, in the space of her canvas, allows forms and colors to embody two things at once and contradictions to survive simultaneously. The element of the mirror is not just an addition to her palette, but is used as a means to implicate the viewer. Zuckerman-Hartung’s unstretched painting counts sewn t-shirts, coat liner, wool, canvas, and dropcloth as its supports. The artist deals in androgyny: She paints with bleach (“The mark of presence is also the mark of absence.”) and denies the abstraction/figuration opposition (“It is a figure/ground issue. In abstraction, the figure and ground begin to flip. That's what’s potent about it, getting your head around that and getting to understand the power of negative space or negativity in general. These flips begin to make the world so much stranger.”).

A younger generation of artists are mixing and matching all that precedes them. Alex Bradley Cohen’s (b.1989) portraits find kinship with both de Kooning and Lemon. The body of his subject Tariq is made up of a spectrum of strokes. Moreover, in the same way that Elaine and Joan left the party together in solidarity, Cohen is imaging the artist community around him, his friends and family. Sable Elyse Smith’s (b.1986) video, born out of a real-time collaboration with a Baghdad-based university student, showcases the failure of language. Smith manipulates video with a painterly quality — utilizing layering, collage, and opacity to refuse a conventional way of looking and understanding. The artist mines the gaps in language and images. Working in the tradition of making paintings on the ground, Vanessa Thill (b.1991) leaves her marks and flows to chance and chemical reaction. The piece on view is composed of coffee, fabric dye, metallic pigment, fake blood, epoxy resin, Elmer’s glue, and two dozen other ingredients found at the dollar store down the block from her studio. In a recent poem titled “Decade Doors,” Thill writes, “Dry tornado/all the ab-ex moves/Disappeared into the weather/dry it out/peel it up.”