Almost

December 10 - January 17, 2010

Stephanie Backes, Rosy Keyser, Jim Lee, Alan Saret, Josh Tonsfeldt, Richard Tuttle

-

Installation view, Almost, 2010

-

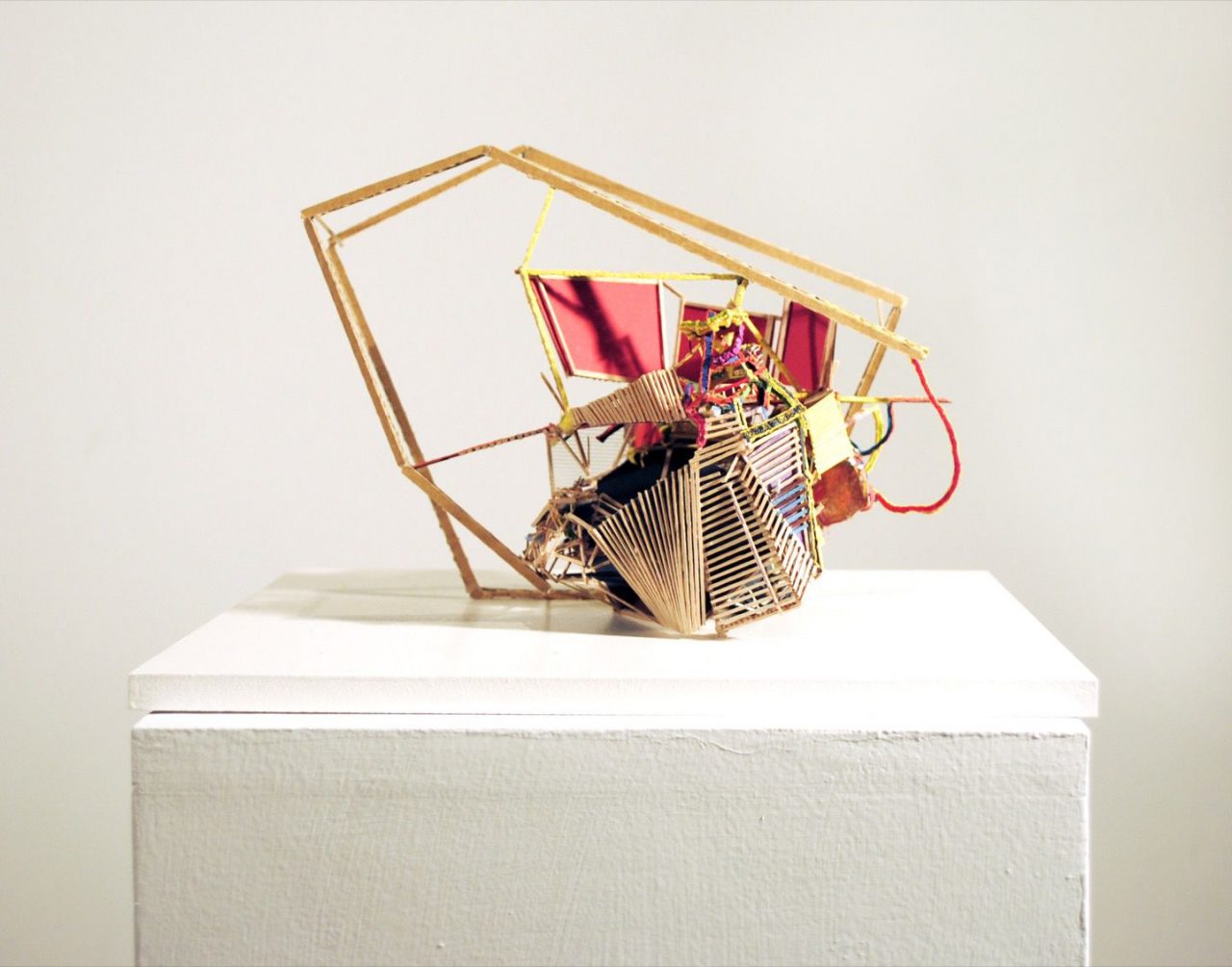

Stephanie Backes

Klappanzer, 2008

Wood, paper, plastic, felt

16 x 22 x 14 cm -

Alan Saret

Infinity Cluster with Red and Dark Green, 1980

Mixed media

30 x 30 x 30 inches -

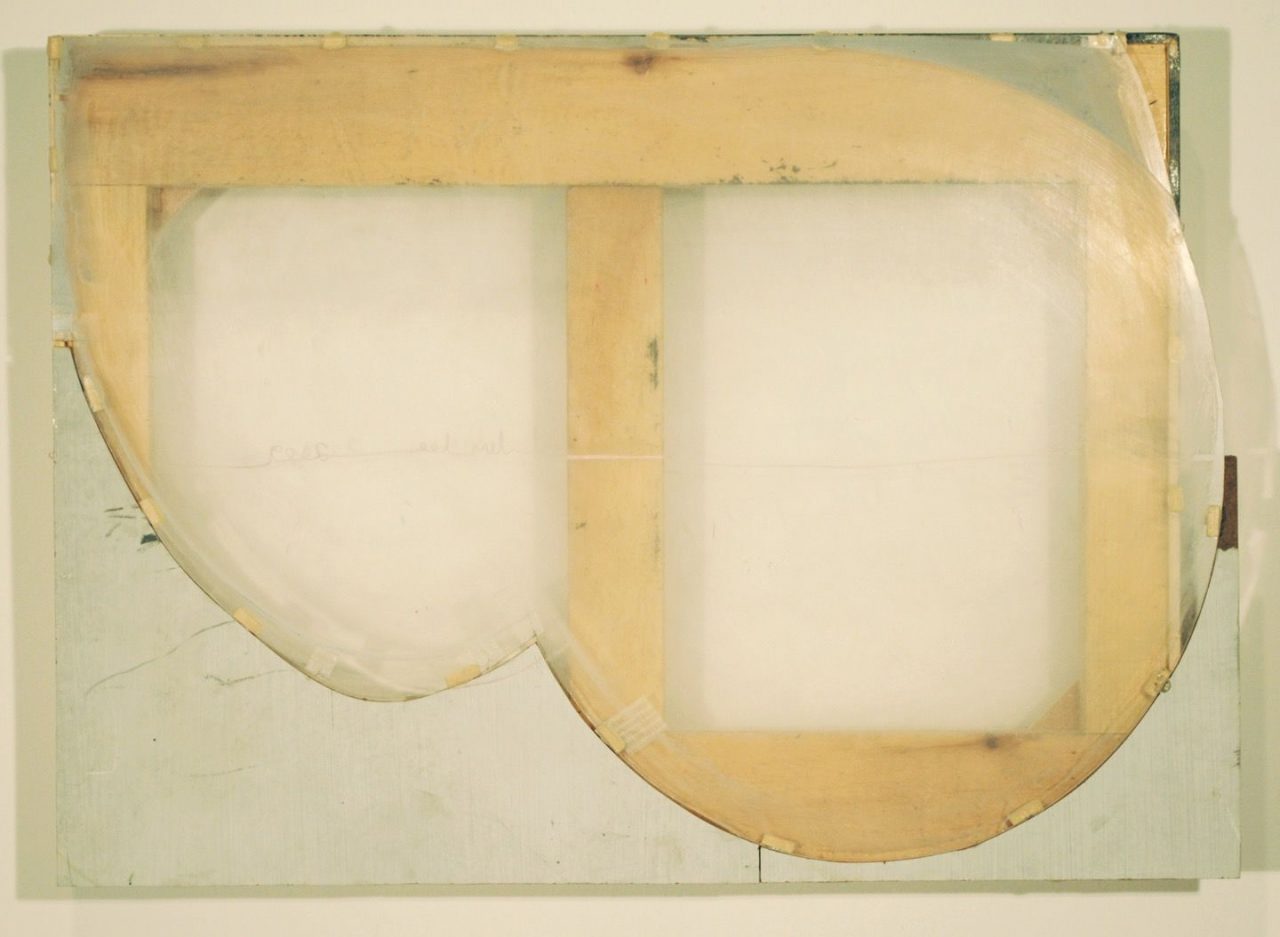

Jim Lee

The Innocent, 2009

Oil on masonite, plexi glass and wire with tape and glue

15 x 21 inches -

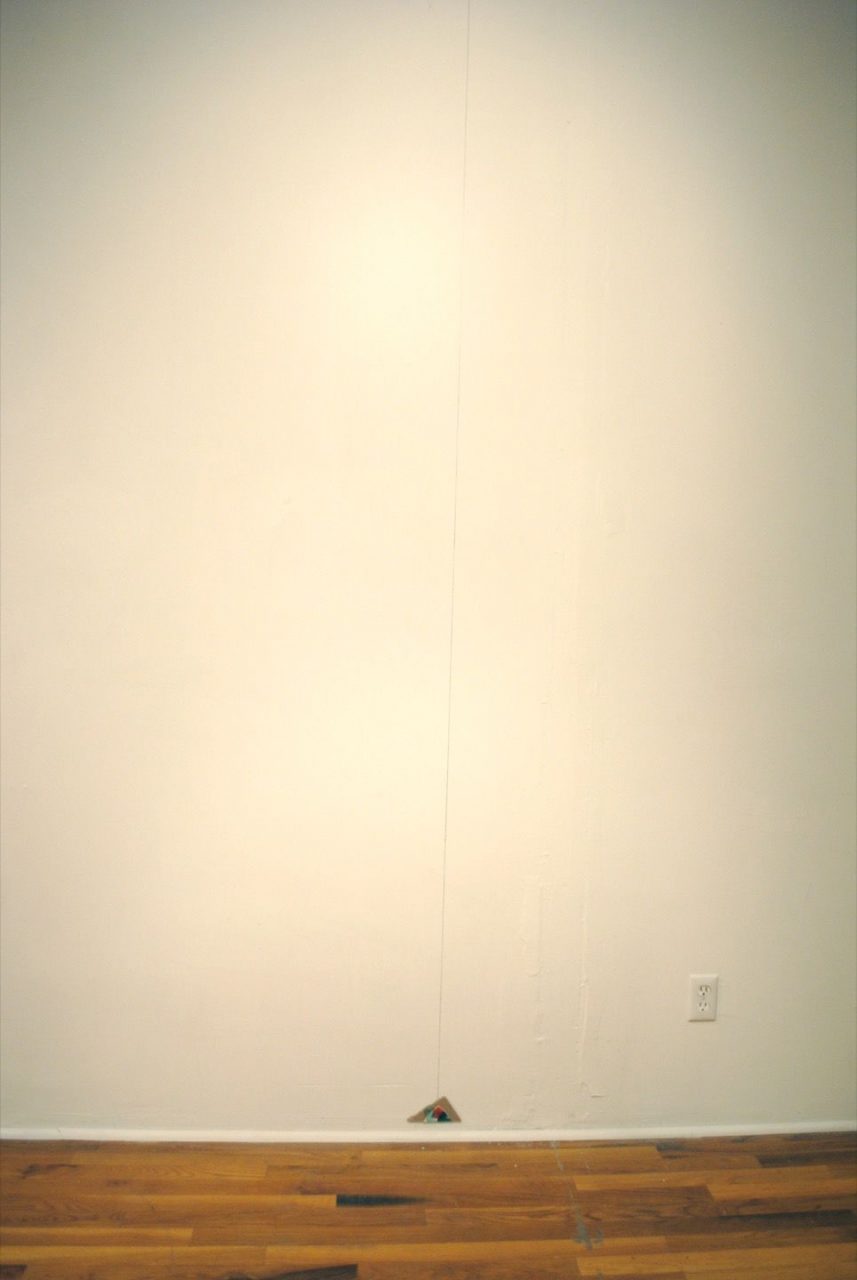

Richard Tuttle

Fiction Fish I, 12, 1992

Acrylic and paper on cardboard, graphite line

2 x 5 inches -

Josh Tonsfeldt

Untitled, 2009

Spray paint and spider web on paper

14 x 11 inches -

Rosy Keyser

Promethian Arrangement (Variation II), 2009

Dye and spray paint on linen

84 x 60 inches -

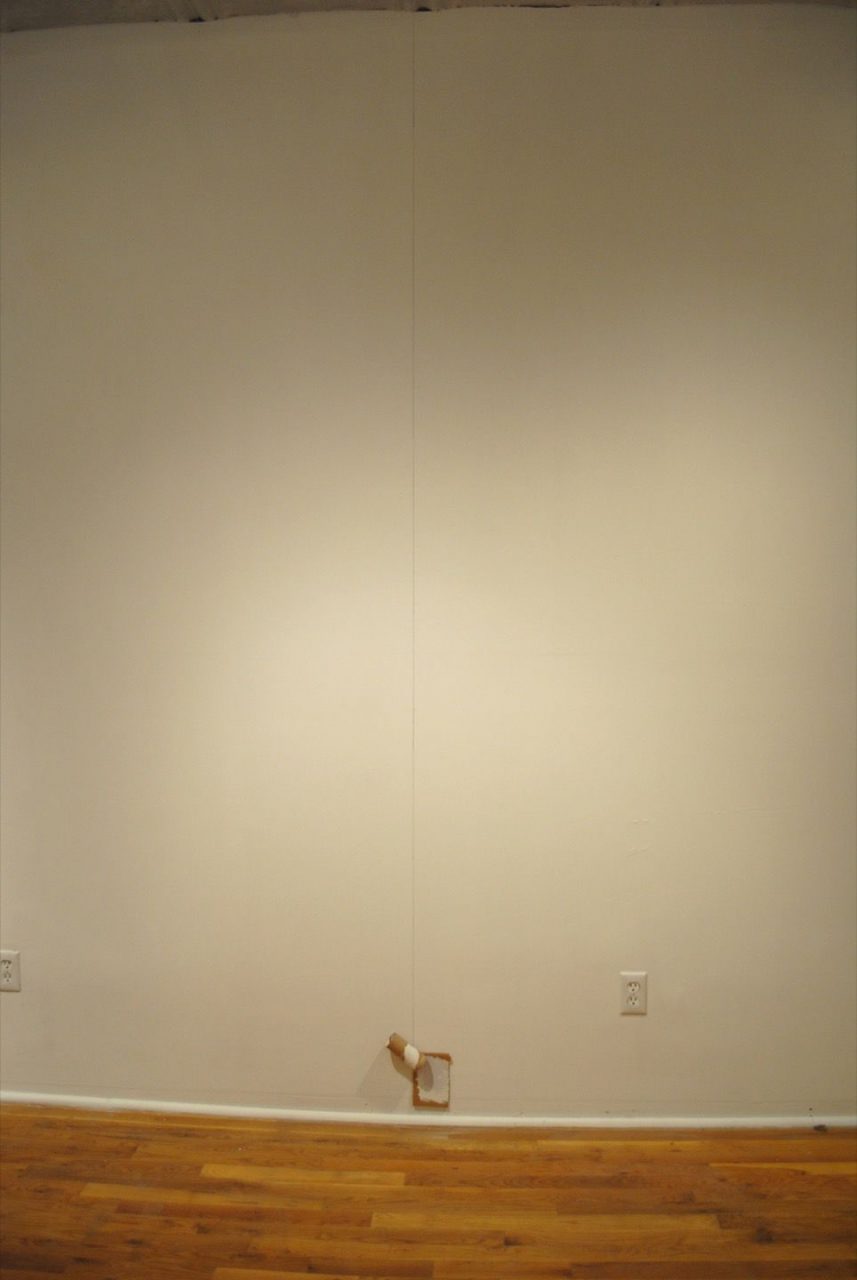

Richard Tuttle

Fiction Fish I, 15, 1992

7 x 8 x 1 inches -

Jim Lee

Untitled (Vertical Offset), 2009

Oil on wood with linen staples and glue

91 x 22 x 2 inches -

Rosy Keyser

Press Release

The exhibition examines questions of stability, as an element contended with, battled against or consciously sought in contemporary art practice. Engaged in both formal aspects of object making and the conceptual layer of artistic production, ALMOST is an exploration of suspension and fragility; it places the viewer into a state of anticipation. Each of the artists participating in ALMOST utilize a variety of found, natural and manufactured materials that may be fragile in and of themselves, in their use, or in their juxtaposition with other elements. The works presented

inhabit a tenuous space; they are at once static objects, while simultaneously offering the illusion of material and conceptual collapse.

There are a number of historical precedents for such work. Cezanne's "finished/unfinished" works are but one example. These works, rather than presenting themselves as competed paintings and drawings —a conceit that in Cezanne's time, was an inherent part of the artist-viewer contract— challenged the notion of finality in art making. Whether the works are or were meant to be completed is a continuing subject of art historical debate, and only further complicates the discussion. The controversy begs a question that is three-fold; whether an artist chooses to present a work as “finished”, whether the viewer perceives a work to be finished, and what completion or lack thereof does to our notion of experiencing art in an exhibition setting. In the twentieth century, Richard Serra's "Prop" sculptures address some of the same questions.

Richard Tuttle's Fiction Fish works, for example, “hang” precariously by a drawn pencil line reaching inches from the floor. Utilizing common household materials such as a toilet paper roll, cardboard and glue, the works evoke humor and humility. For Tuttle, all artwork, and all of life for that matter, is a kind of drawing. Additionally, what isn't physically present in a work of art is just as significant as what is. The walls, shadows and the diminutive humble objects of which these works are composed, are inextricably linked. By intentionally hanging works in an extraordinarily high or low position on the wall, Tuttle invites the viewer to explore the spatial dynamics of the room in relationship to the object. In this manner, architecture too becomes pure line.

Constructed with substances such as sawdust, aluminum, rope, obsidian and an assortment of paint mediums, Rosy Keyser's highly tactile and physically substantial paintings engage the viewer in a post-apocalyptic opera. Masterfully subtle in her use of tone, Keyser extracts as much color from her blacks as Ad Reinhardt once did with his "Ultimate Paintings." Keyser's work compels us to accept the slow burn. While viewing her paintings, time evaporates. Poetic at the core, her work suggests a metaphorical connection between our psychological and natural worlds.

Jim Lee's work puts a glaring spotlight on the creative process, and equally on its dismantling. Oddball found objects are combined in a manner that reveals the guts of a project; Lee seductively turns the insides out. Art materials are deliberately used in ways they weren't intended to be. Household glue, for example, is used not so much to hold disjointed pieces together as it is to validate it as a medium in and of itself. For Lee, material hierarchy is turned on its head. The more beaten and destroyed the found scrap, the more useful and alluring it becomes. Jim Lee's work audaciously celebrates the "factory reject" and the realm of cast-offs.

Alan Saret's 'anti-form' wire sculptures are purposely mutable. Utilizing an array of industrial wire, Saret creates loose tangles and threadings that have no specific designated form. While the works may suggest organic matter, from webs to dreadlocks to nests, Saret is interested solely in physical properties, namely how a work hangs, bends and knots up under its own weight. In a sense, Saret shares the creative act with the art object itself by allowing it to do what it will do without his intervention.

Negotiating the space between his rural and urban existences, Josh Tonsfeldt creates pieces that capture nature in its rawest form, and injects them with a dose of city grit. In one example, Tonsfeldt employs spider webs that he found in his family's abandoned horse barn. To them he added a graffiti-like patina. The resultant forms become illuminated by the white sheets of paper upon which they were placed. The webs are frozen, and yet remain sticky. As air moves through them, they appear to vibrate. Much like the important 1969 work Reticularea by Gertrude Goldschmidt, the webs are simultaneously an amalgam of drawing, sculpture and architecture.

Stephanie Backes' sculptures belie their intrinsic materials. Wooden rods twist, thread-like surfaces take on the appearance of wings and drops of glue pass for water. In Backes' imaginative work, biological forms meld with architecture. Small in size, these colorful hybrids seem to be evolving and wildly gyrating. Backes extols the delicacy of the components and construction of her work while also pushing her forms into a futuristic mass.