In Sickness and In Health

July 12 - August 31, 2020 | Launch Viewing Room

David Altmejd, Pablo Amaringo, Kari Cholnoky, Louise Despont, Minnie Evans, Harun Farocki, Guo Fengyi, Luchita Hurtado, Tetsumi Kudo, Emma Kunz, Guadalupe Maravilla, Badrinath Pandit, Daniel Rios Rodriguez, Shawn Thornton, Melvin Way

Curated by Chris Wiley

-

Installation view, Emma Kunz, Work No. 003, n.d.

-

Guo Fengyi

SARS 1, SARS 2, SARS 3, and SARS 4, 2003

Ink on rice paper

60 1/2 x 18 inches, 58 x 18 inches, 58 x 18 inches, and 59 x 18 inches

Courtesy Long March Space, Beijing -

Installation view, Pablo Amaringo, Jehua Supai, 2004, and Unai Shipash, 2006

-

Installation view, Shawn Thornton, Brahaastra for a New Age (UFO/Time Machine), 2010-2013, and Homemade Space Suit of Living Information (Self Portrait), 2016

-

Installation view, Louise Despont, First Flight, 2018, and Dilution, 2019

-

Installation view, Minnie Evans, Untitled, 1967; Untitled, 1962; and Untitled, 1962

-

Anonymous Photographer

Lourdes, France: the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes: crutches left behind by pilgrims, amassed on the walls of the cave., ca. 1937

Photoprint

6 1/4 x 8 1/2 inches

Wellcome Collection, London -

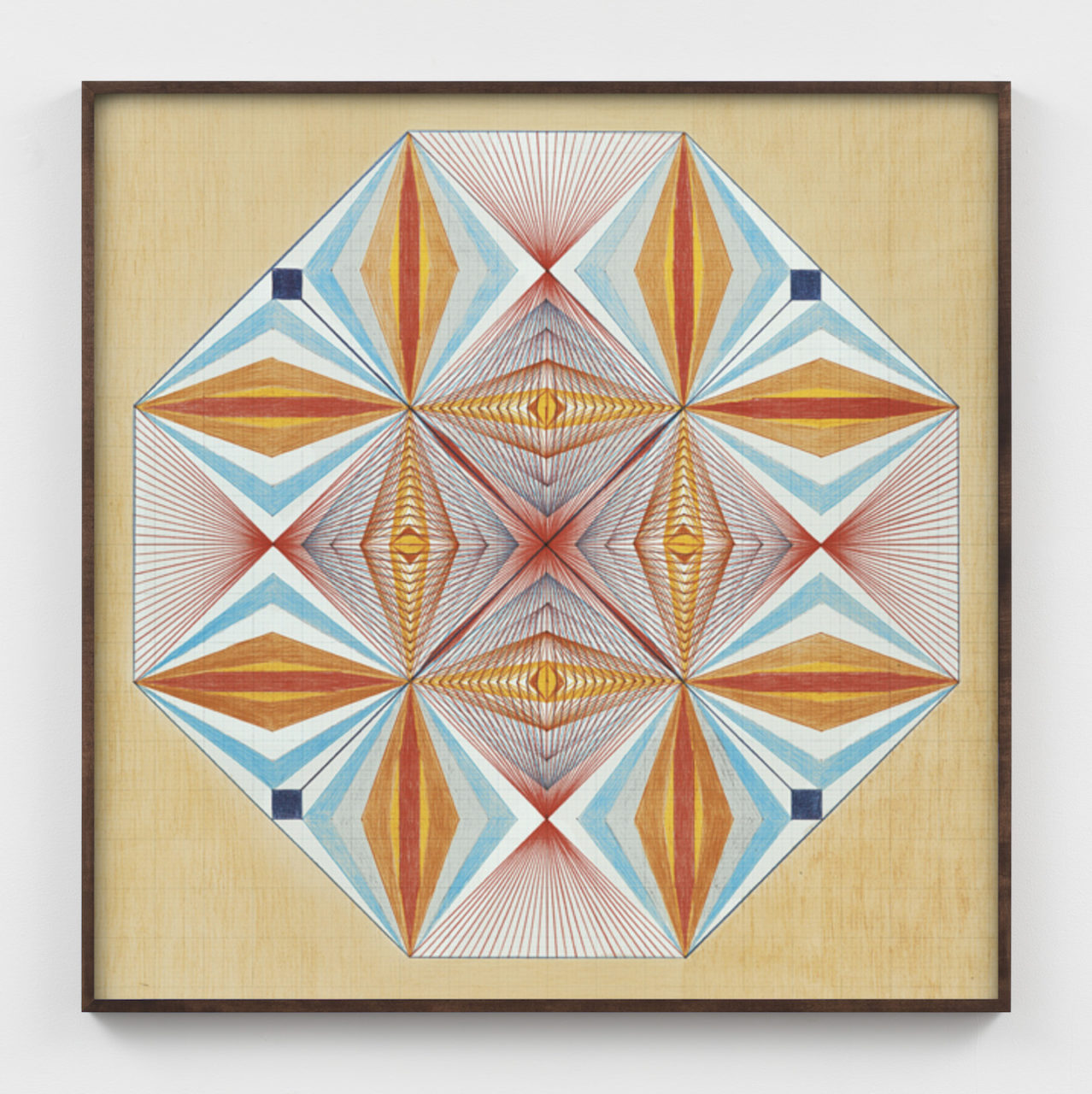

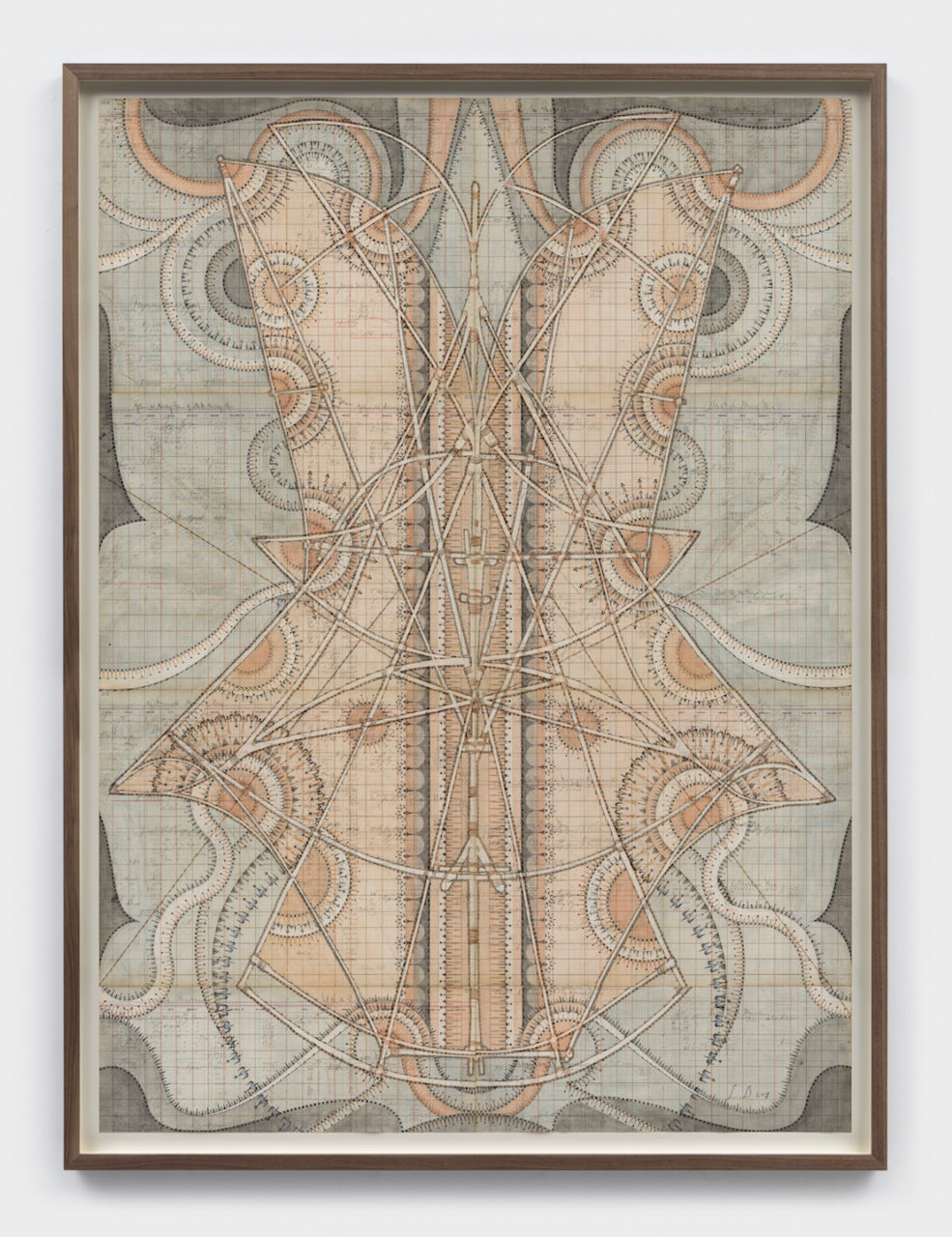

Emma Kunz

Work No. 003, n.d.

Oil crayon on graph paper

with brown lines

37 3/4 x 37 3/4 inches

© Emma Kunz Zenstrum -

Kari Cholnoky

Machinator, 2020

Faux fur, acrylic, collage, epoxy putty

26 x 52 x 14 inches

kcholnoky001 -

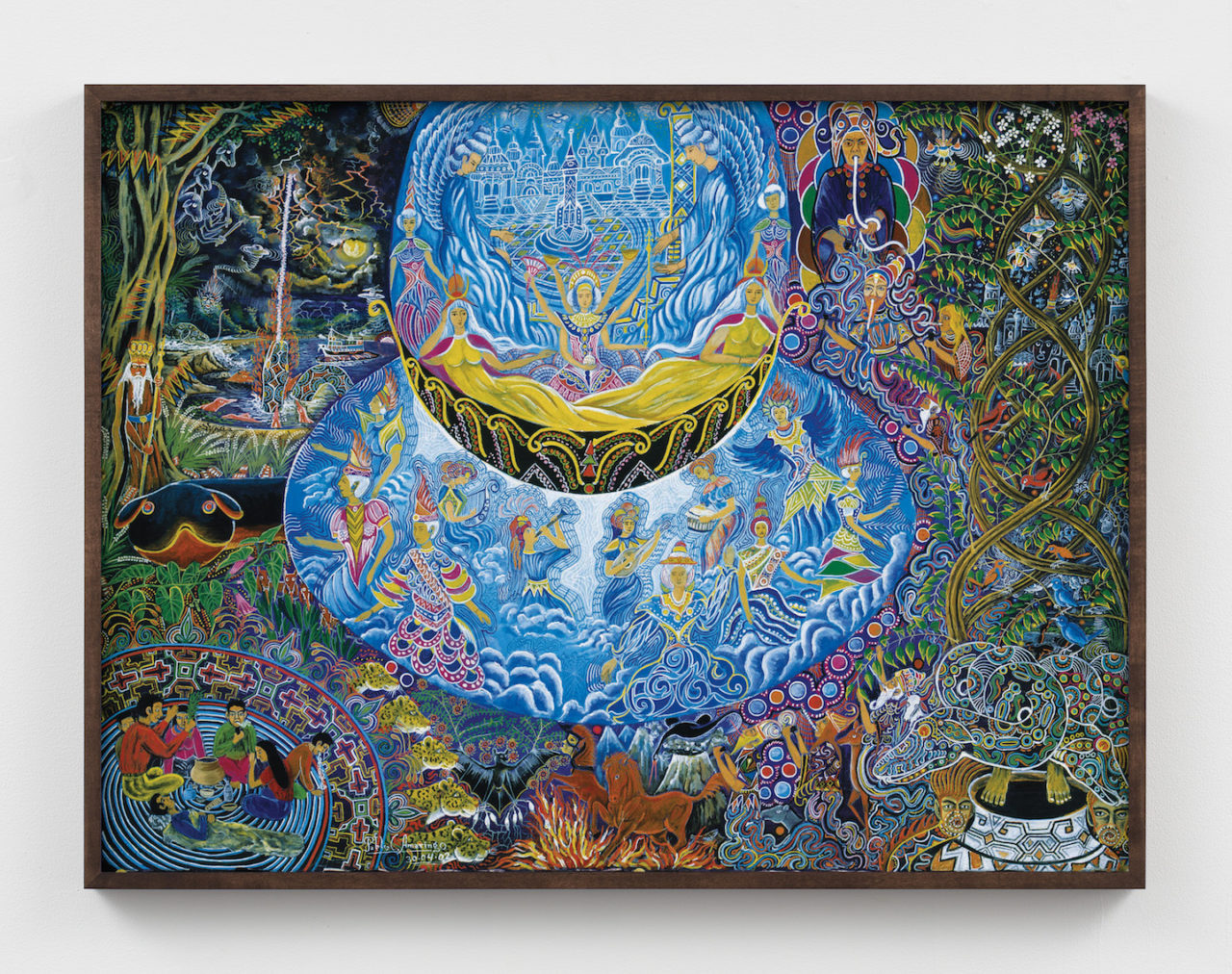

Pablo Amaringo

Unai Shipash, 2006

Glicee Print

22 1/2 x 29 3/4 inches -

Pablo Amaringo

Jehua Supai, 2004

Glicee Print

21 1/4 x 16 inches -

Tetsumi Kudo

Votre Portrait, 1970-79

Mixed media

19 5/8 x 18 1/8 x 9 7/8 inches

© Hiroko Kudo, the Estate of Tetsumi Kudo, ADAGP Paris, ARS New York, 2020

Courtesy Hiroko Kudo, the Estate of Tetsumi Kudo, Tokyo and Hauser & Wirth -

Minnie Evans

Untitled, 1962

Ink and colored pencil on paper

12 x 10 inches

Private Collection -

Minnie Evans

Untitled, 1967

Oil, ink, pencil, and colored pencil on canvas

22 x 27 inches

Private Collection -

Minnie Evans

Untitled, 1962

Ink and colored pencil on paper

12 x 10 inches

Private Collection -

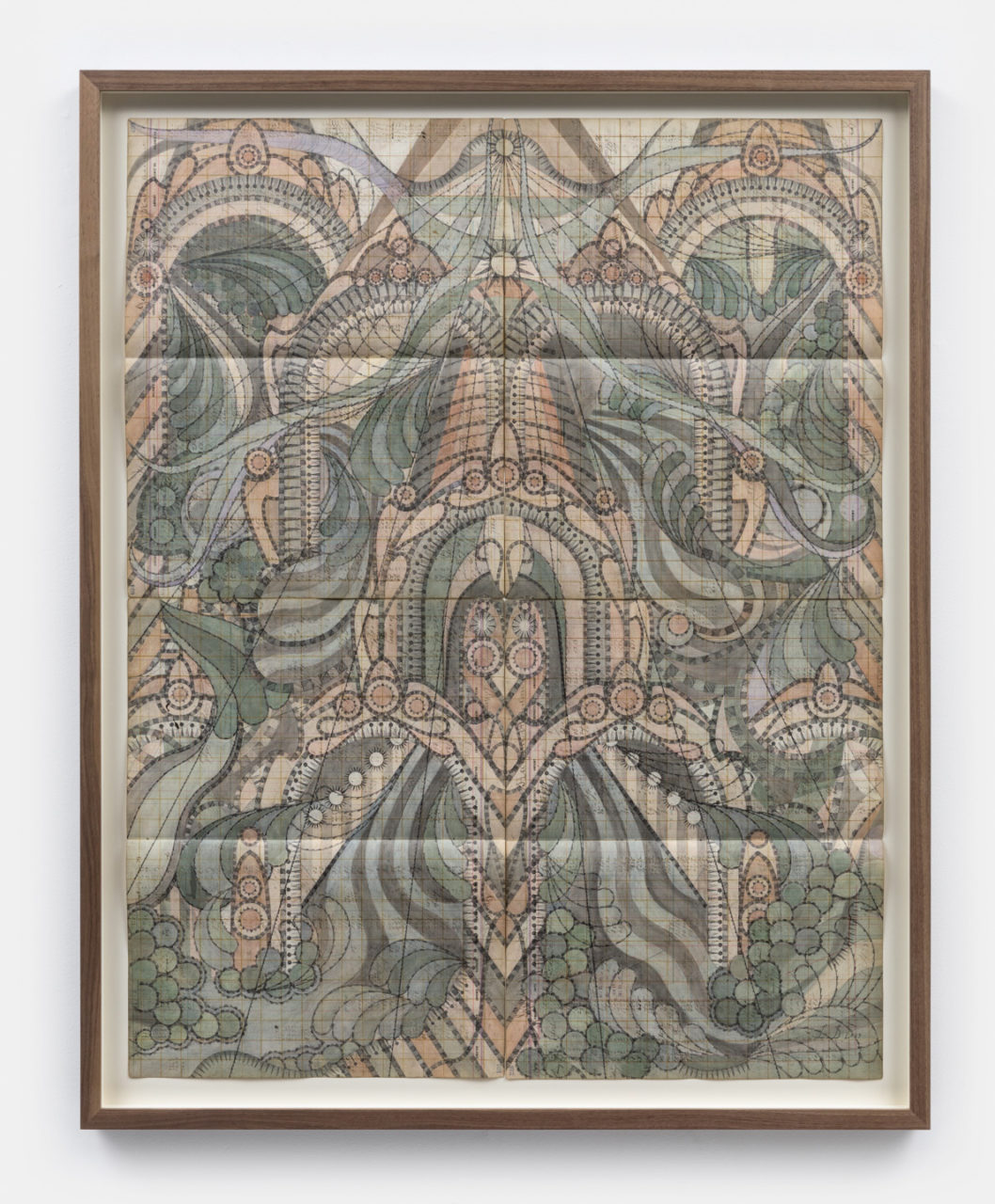

Louise Despont

Dilution, 2019

Graphite and colored pencil on antique ledger book pages

47 1/4 x 37 inches

ldespont1001 -

Luchita Hurtado

Untitled (Birthing), 2019

Mixed media on paper

22 x 15 inches -

Louise Despont

First Flight, 2018

Graphite and colored pencil on antique ledger book pages

65 1/2x 47 3/4 inches

ldespont0298 -

Melvin Way

89, 2013

Ink on paper

6 x 5 inches

mway0001 -

Melvin Way

Mile foot per second, c. 2015

Ballpoint pen on paper

6 x 3 1/4 inches

mway0002 -

David Altmejd

Crystal System, 2019

Expanded polyurethane foam, cement, resin, epoxy clay, epoxy gel, synthetic hair, acrylic paint, quartz, steel, coconut shell, glass eyes, paper, graphite, pearl mica flake and glass gemstone

28 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 17 inches

Private Collection

Courtesy White Cube -

Guadalupe Maravilla

Disease Thrower #1, 2019

Mixed media sculpture

97 x 56 x 63 inches

Private Collection

Courtesy of Guadalupe Maravilla and P·P·O·W, New York -

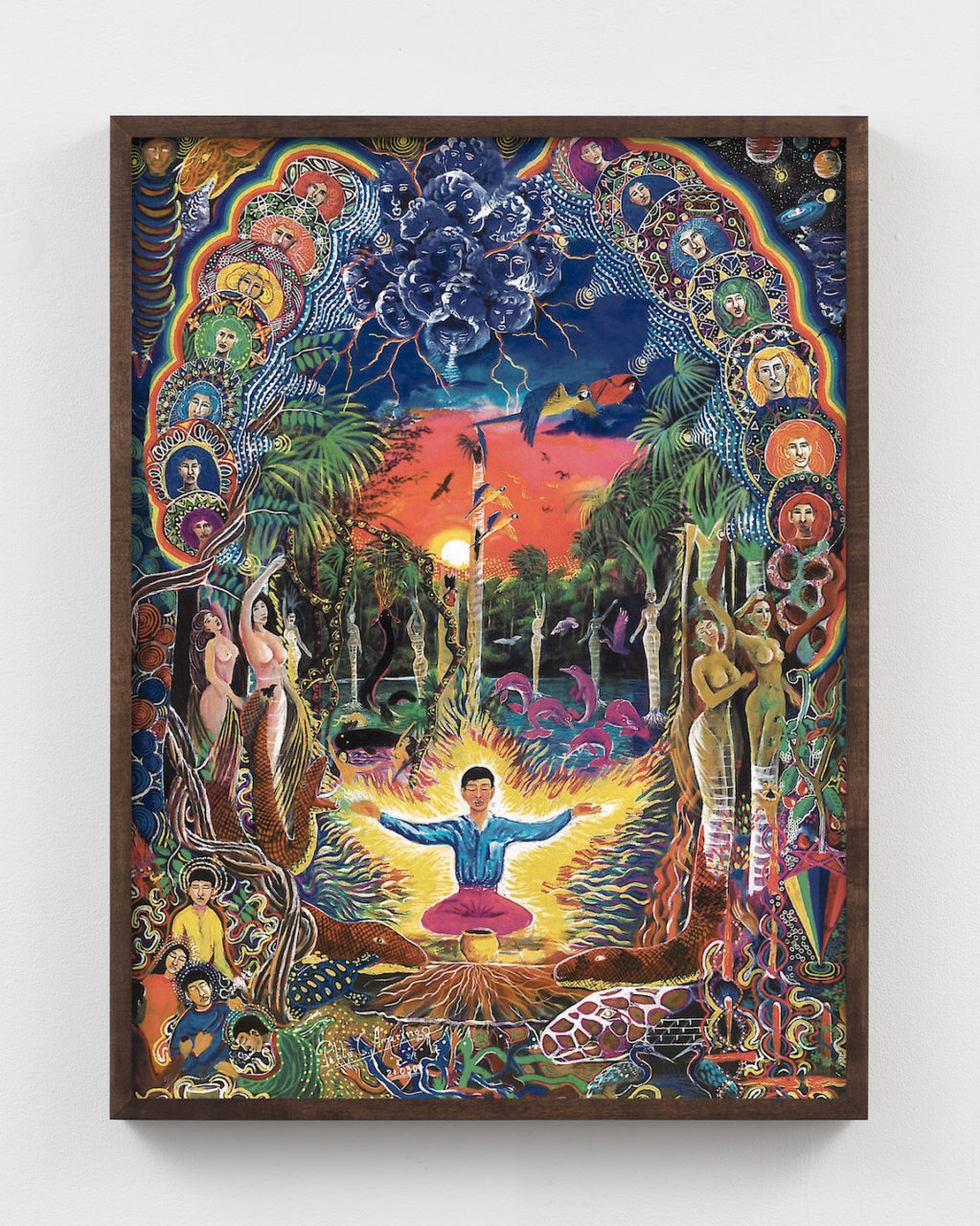

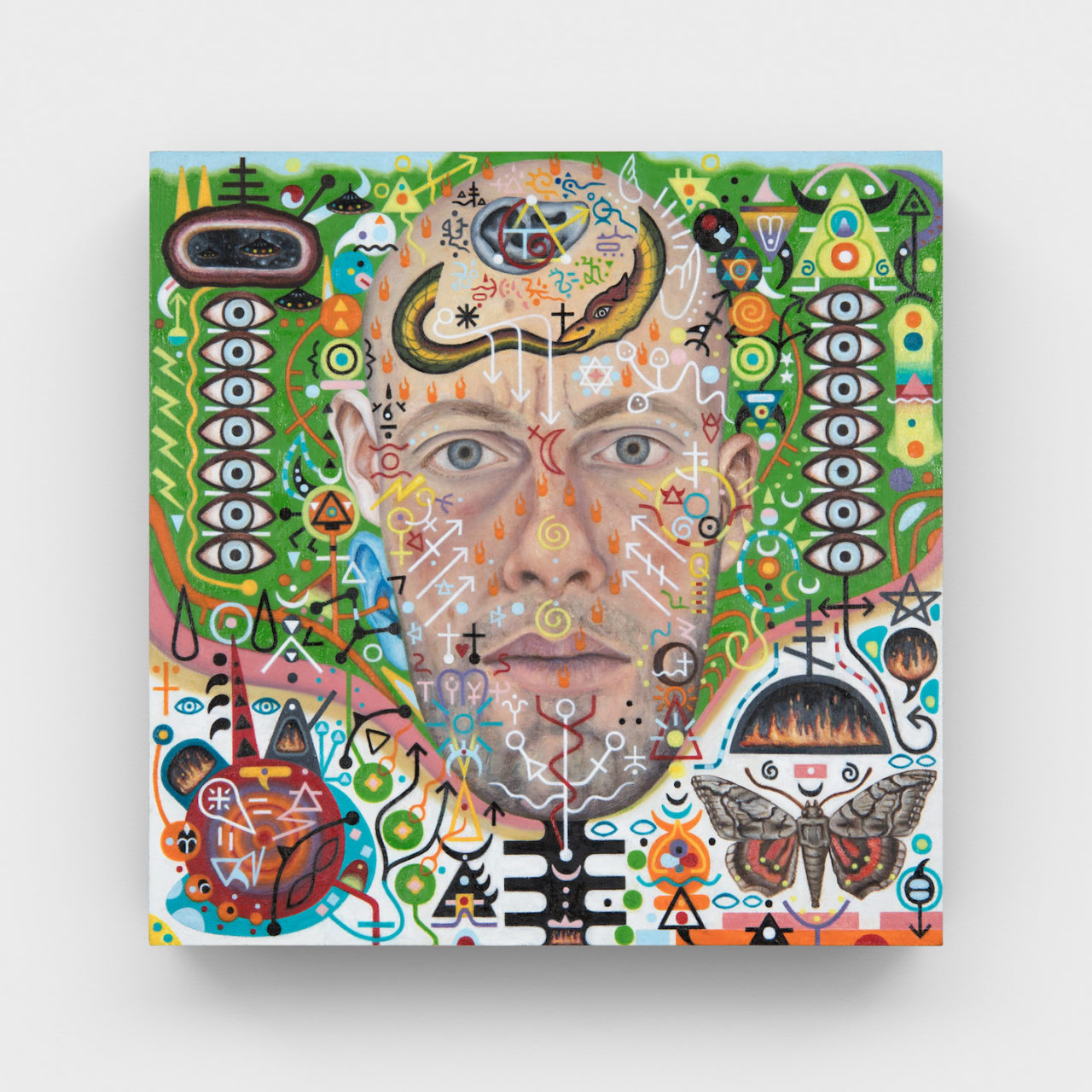

Shawn Thornton

Homemade Space Suit of Living Information (Self Portrait), 2016

Oil on panel

8 x 8 inches

sthorton0002 -

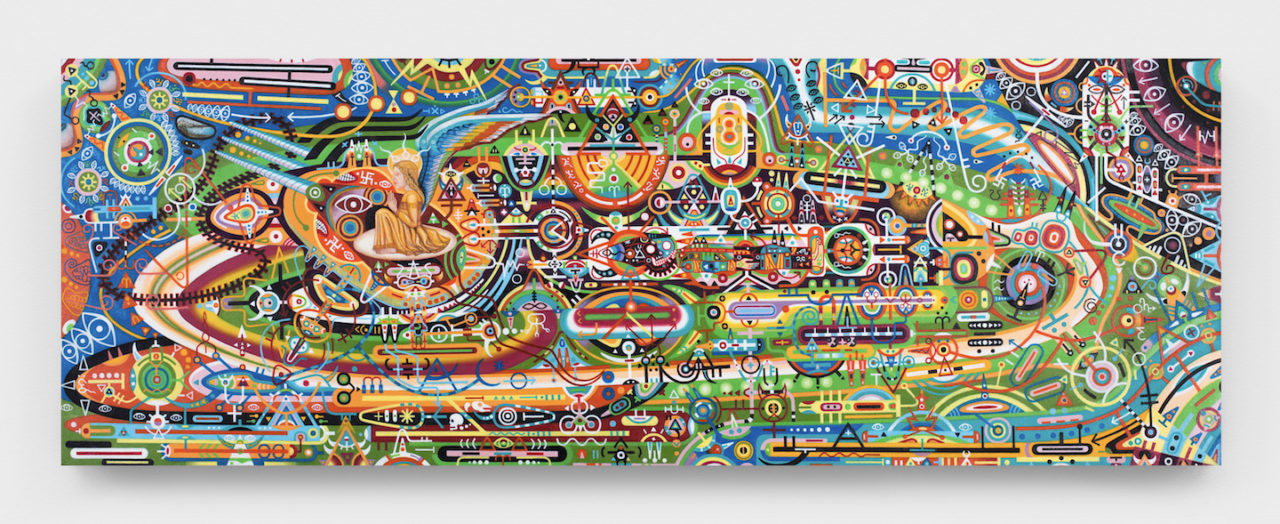

Shawn Thornton

Brahaastra for a New Age (UFO/Time Machine), 2010-2013

Oil on panel

9 x 27 inches

sthorton0001 -

Daniel Rios Rodriguez

Grappler, 2017

Oil, Flashe, wood, rope, nails, and found objects on panel 9 1/2 x 14 inches

drodriguez0128 -

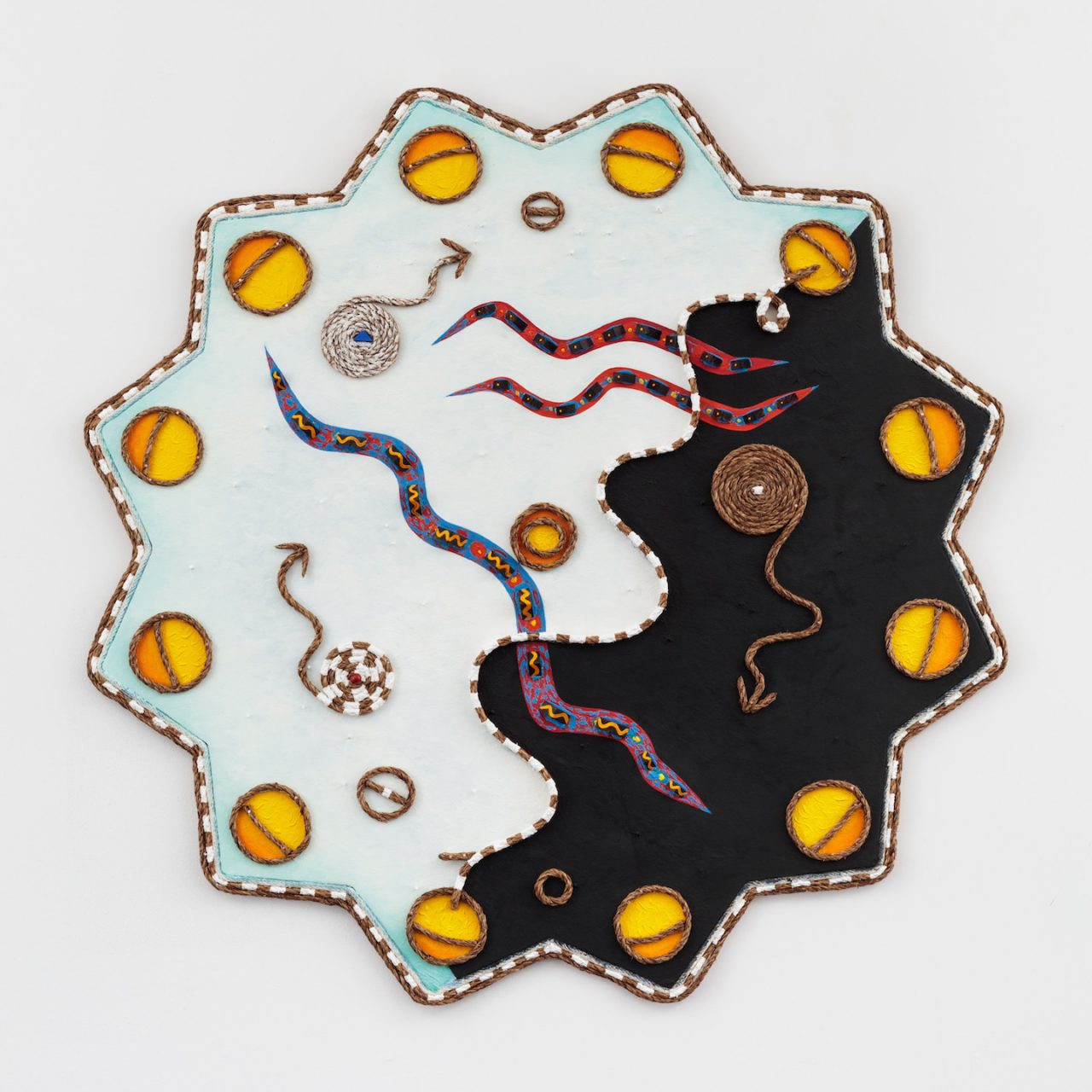

Daniel Rios Rodriguez

Casi un Hechizo, 2018

Oil, wood, nails, rope, Texas Mountain Laurel bean on wood panel

44 1/2 x 44 1/2 inches

drodriguez0141 -

Daniel Rios Rodriguez

Untitled, 2019

Oil, copper, rope, and limestone with wood frame

23 1/4 x 20 3/4 inches

drodriguez0169

Press Release

With sickness on all of our minds, In Sickness and In Health looks to the ways that art can heal.

Since prehistory, art has been used as a method to materialize the demons that haunt the shadows of our psyches and our societies, as well as the unseen forces that ravage our bodies. Exteriorizing these scourges performs a kind of magic. By unearthing them from the body, we feel we can gain some purchase on them: they become effigies that can be prayed to, burned, or offered our sacrifices; or they become totems that can stir the empathy of the unafflicted, and rouse a sense in lonely sufferers that others feel their pain.

Guo Fengyi is a self-trained artist whose work springs from the visions she experiences while practicing Qi-gong, an ancient body posture and mediation technique that she became devoted to after debilitating arthritis forced her to leave her job in a factory. Her series of SARS drawings, which depict looming, malevolent spirits, were a response to the yearlong outbreak of the disease in 2003, which forewarned our current crisis. Tetsumi Kudo’s twisted visions of mutant nature and bodily horror were fashioned by a crisis of a different kind: the atomic bombing of his native Japan. He asks us to stare darkness in the face, but tempers it with a dash of jet-black humor to keep us from going over the brink. In a similar vein, Kari Cholnoky makes sculptural reliefs that resemble a microscopic view of malignant growths and terrifying microorganisms, but festoons them with collage elements that she trawls from the depths of the Internet. Harun Faroki’s video Transmission (2007) is a document of rituals of remembrance and penitence that surround monuments and statues, from pilgrims touching the feet of St. Peter in the Vatican Basilica in Rome, to loved ones making rubbings of the names of the departed at the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington D.C.

Shawn Thornton has had visceral experience with illness—he successfully fought off a rare brain cancer of the pineal gland—but it somewhat paradoxically lead him to a more expansive sense of reality. His cancer triggered wild hallucinations (the clinical psychologist Rick Strassman has put forth the popular theory that the pineal gland produces DMT, one of the most potent psychedelics known to humankind), which informed the meticulously detailed, cryptically metaphysical paintings that he made both during his illness and after he was cured. The mind-bending busts of the sculptor David Altmejd seem to be similarly suspended in a liminal space between disease and transcendence, with wounds that spout glittering crystals and jittery, time-lapse-like duplications that seem to point to either his figures’ imminent merger with the numinous realms beyond, or the beginning of the complete breakdown of the mind, the body, or both.

Art has also long acted as a salve for our spiritual and physical ills. Today, we have a tendency to take this function somewhat metaphorically. Art can, in this mode of thinking, furnish the impoverished houses of our minds with gorgeous psychic furniture, or alchemize our collective pains into objects or experiences of great beauty. But an originary, magical sense of art’s power lingers: talismans ward off evil, mandalas catalyze states of meditative insight, and holy relics offer cures.

The kaleidoscopic drawings of Swiss mystic Emma Kunz, which she used to channel medicinal knowledge and gain metaphysical insight, were used as aids in her healing rituals, during which they were placed on the floor between Kunz and her patient. Louise Despont, for whom Kunz is a signal inspiration, makes intricate pencil drawings on antique ledger paper that pulse with some of the same mysterious energies. Like Kunz, Pablo Amaringo also worked in the healing arts, practicing as an ayahuasca shaman deep in the Peruvian Amazon. His lush, vibrant paintings are purportedly documents of the visions that he experienced over his decades of work with the potent psychedelic brew. Guadalupe Maravilla’s work is similarly balanced at the juncture between Shamanic medicine and art. Maravilla fled the Salvadorian Civil War and came to the United States as an undocumented immigrant at the age of nine, and much of his practice focuses on healing rituals aimed at Indigenous and undocumented peoples. His series of Disease Throwers, however, have their origin in personal healing: when Maravilla was being treated for colon cancer, he discovered the salubrious effects of gong meditation. He now performs on the gongs integrated into his sculptures to facilitate the heath and wellbeing of others.

In a related register to Kunz’s sublime geometries, the Tantric paintings made by Badrinath Pandit following the traditions of the Indian state of Rajasthan were painted in order to aid in mediation, and are rich with ancient symbolism relating to the pantheon of Hindu deities. Though Daniel Rios Rodriguez’s thickly impastoed paintings spring solely from the confines of his mind rather than a religious tradition, they nevertheless radiate veiled spiritual import, and have a dense symbolic language all their own. The self-taught artist Melvin Way’s dense drawings of imaginary mathematical equations and chemical formulas form a similarly complex personal language, which seems to be his attempt to dissect the fundamental nature of reality, perhaps with an eye to setting it right.

In art, just as in healing, there is always room for miracles. Minnie Evans, a self taught artist who was the descendant of enslaved Trinidadians in North Carolina, heard a voice tell her to “draw, or die” when she was forty-three. Following that command for much of the remainder of her life, Evans channeled drawings of fantastically headdressed Gods and Goddesses, phantasmagorical plant life, and otherworldly spirits, which she claims were visions given to her directly by God. Somewhat like Evans, a revelation was also visited upon the young Bernadette Soubrious, a peasant in the French town of Lourdes, in 1858. Near what is now called the Grotto of Massabielle, Soubrious repeatedly saw visions of the Virgin Mary, who told her that a spring would appear at the site where pilgrims could come to drink curative water. Ever since, the sick have ventured to the site to be healed by drinking holy water, and the walls of the grotto have been hung with the cast off crutches of the cured, depicted in a photograph from 1937 that is included in the exhibition. Luchita Hurtado, whose work went almost completely undiscovered until she was ninety-six, has recently been producing a body of work concerned with the dangers of climate change. Concurrently, however, she is also making another series of works, in which she depicts herself giving birth. Though the prospects of the world’s future look bleak, she seems to be saying, there is always hope that a new world can be born.